Thomas Friedman’s Op-Ed: “Win, Win, Win, Win, Win”: Making the Systems Visible

In a recent New York Times Op-Ed, Thomas Friedman argues that the second most important rule to energy innovation is “a systemic approach.”

In a recent New York Times Op-Ed, Thomas Friedman argues that the second most important rule to energy innovation is “a systemic approach.”

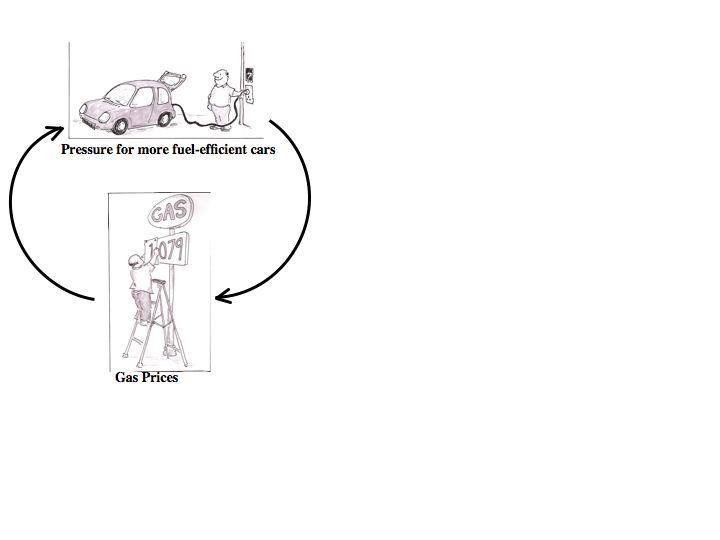

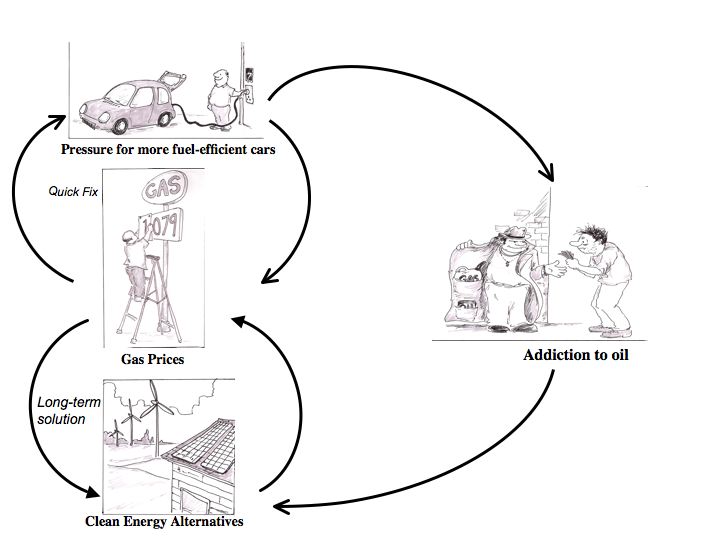

In this article, Friedman talks us through a recurring “play,” in which gas prices, consumer demand full-efficient cars and “petro-dictators” all play a part. According to Friedman, the play goes like this:

“Which play? The one where gasoline prices go up, pressure rises for more fuel-efficient cars, then gasoline prices fall and the pressure for low-mileage vehicles vanishes, consumers stop buying those cars, the oil producers celebrate, we remain addicted to oil and prices gradually go up again, petro-dictators get rich, we lose. I’ve already seen this play three times in my life. Trust me: It always ends the same way — badly.”

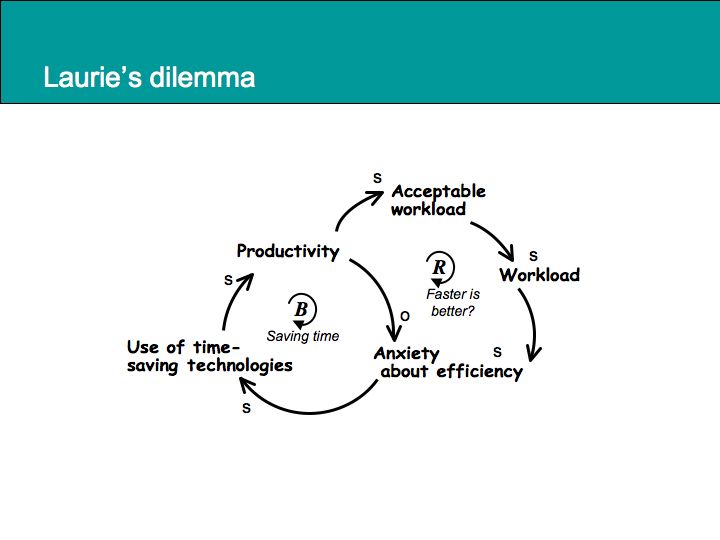

OK. So, let’s look at the system (or set of interrelationships) behind the “Win, Win, Win…” play. Friedman identifies several interconnected elements:

Gas prices (go up and down)

Pressure for more fuel-efficient vehicles (goes up or down)

Here is a very simple map of the system:

If we walk around the loop, it reads like this:

If we walk around the loop, it reads like this:

As gas prices go up, pressure to increase fuel efficiency goes up.* In the short term, the reduced demand on gasoline, means more supply and eventually gas prices fall.

What happens to the demand for more fuel-efficient cars when prices fall?

It falls off. And for those who may have been driving less, start to drive more. Why? The pressure’s off.

Where else have you seen this kind of pattern?

It reminds me of the ups and downs of dieting and exercise. You exercise and loose weight. Great. End of story, right? Well, not usually. Often, when we lose the weight, the pressure’s off, so we ease up a bit. And over time, we gain the weight back and we start to diet again.

If we go back to our occasional gasoline “diet”, there’s more to the story. Our dependency on the symptomatic solution, in this case, foreign oil, keeps us in a state of addiction, and so, less focused on more fundamental solutions, one of which is getting off foreign oil and onto clean energy alternatives. If we look at this pattern through the lens of a system archetype called “shifting the burden” it might look like this:

Here’s the rub: The upper loop (the short-term solution) works, in the short term. It’s insidious though. Because it works, it takes us away from more fundamental solutions. A classic example of a shifting the burden archetype is alcohol and drug use. Feeling stressed? Have a glass of wine. Or two. Over time however, this response to stress can have unanticipated side effect, such as greater fatigue, poor health, and addiction. The burden for solving the problem or making the pain go away is shifted onto the upper loop.

What might be a longer-term, more fundamental solution to stress? For some, it may be making an adjustment to workload, or getting more sleep. For others, it might mean increasing how much they exercise or reconnecting with friends.

So what can we do? Perhaps one step is to remember what long-term solutions look like. Look at older people in China practicing Qigong in the parks, day in and day out. That’s a long-term, mind-body health solution. Hiring in outside consultants can be a short-term solution. Developing skills and leadership capacity in existing staff is a long-term solution.

So what else can we do? Another simple step is to start paying attention to the recurring patterns, or the “plays” as Friedman calls them. If we’re able to see shifting the burden patterns, or a host of other recurring systems patterns around us, for what they are, we’re more likely to be able to step out of the habitual patterns of thought and action associated with them. When we can do this, we’re more able to work with and eventually change those patterns.

To explore these dynamics further, check out the Friedman project netsim created by myself and my colleague Chris Soderquist.

*Prices need to stay up a while for this pressure to have a significant and lasting impact.

— Thank you to Dave Smyth for creating these wonderful illustrations.