Why Bucky, and why now?

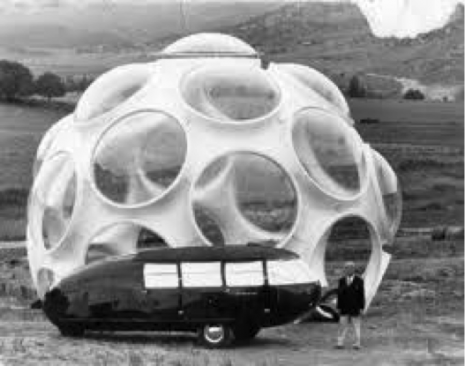

I’ve finished the manuscript for a children’s biography about Buckminster Fuller, and now I wait. The editors in New York City and beyond are chewing him over, deciding if today’s middle school kids will find “Bucky” — most famous for his geodesic domes — interesting, compelling, worth their time.

I, of course, will talk to anyone and everyone about Bucky (I’ve written about him here). Somehow I managed to weave him into a conversation with the cashier at the grocery store the other day. My kids think I’ve lost it. I now call my dog “Bucky” despite the fact that his name is Rugby. The walls of my office are plastered with sketches of Bucky inventions: a fly’s eye dome, a 4D tower delivered by zepplin, rowing needles, a mechanical jellyfish.

So, why am I so hooked?

For me, a twenty-year plus systems educator, one of the most compelling connections is Bucky’s focus on synergy.

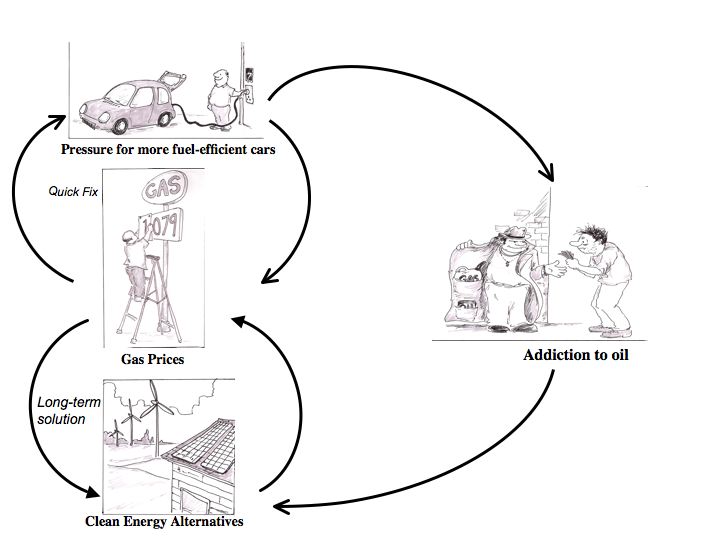

Over forty years ago, Bucky popularized the term, reminding audiences around the world that synergy was “… the only word in our language that means behavior of whole systems unpredicted by the separately observed behaviors of any of the system’s separate parts or any sub-assembly of the system’s parts. There is nothing in the chemistry of a toenail that predicts the existence of a human being” (Fuller, Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth, 1969, p. 78). One of the many benefits of understanding and even designing for synergy, is the opportunity to get off that problem solving treadmill, where our “solutions” often only create more problems or make the original problem worse. (See more benefits here).

Looking back at myself as a student forty years ago, my curriculum was for the most part compartmentalized: science was taught in one class, math in another, English in yet another, and never the twain shall meet. Such a fragmented approach reinforced the notion that knowledge was made up of many unrelated parts, leaving me with little opportunity to see recurring patterns of behavior across subjects and disciplines, to look for synergies, or for that matter, to think or talk about “whole systems.”

My teachers were preparing me for a world in which “new technologies” like the computer were just beginning to play a role, and though I didn’t know it at the time, the middle-aged gentleman teaching “computer science” was desperately trying to stay one step ahead of his eager students. With the shock of the gas crisis in the 1970s, came a nascent awareness of the relationship between non-renewable resources and population growth (what we call carrying capacity today).

It was a world that author and New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman describes as being “characterized by one overarching feature—and that was division. That world was divided-up, chopped-up place, and whether you were a country or a company, your threats and opportunities in the cold war system tended to grow out of who you were divided from. Appropriately, this cold war system was symbolized by a single word—wall, the Berlin Wall.” (Friedman, Longitudes and Attitudes: Exploring the World After September 11, 2002, p. 3).

Today, our world has shifted. We’ve gone from an international system built around division and walls to a system increasingly built around integration and webs, a shift Friedman aptly describes here:

“The globalization system is different. It also has one overarching feature and that is integration. The world has become an increasingly interwoven place, and today whether you are a company or a country, your threats and opportunities increasingly derive from who you are connected to. This globalization system is also characterized by a single word –web, the World Wide Web.” (Friedman, Longitudes and Attitudes, pp. 3–4).

Today’s children are growing up in a world of webs and networks, of increasing interdependence and multiculturalism, of shrinking global borders, and of even more limited natural resources. For students of today, nothing exists in isolation. More and more of the pressing challenges children see in the headlines—global warming, economic breakdowns, food insecurity, institutional malfeasance, biodiversity loss, and escalating conflict—are generated by complex human systems.

Bucky's early sketches of a light-weight aluminum 4D tower, just one of many examples of Bucky's efforts to "do more with less"

Indeed our lives are embedded in systems.

Here’s the wake-up call: Many of us were not explicitly taught skills related to understanding synergy, or for that matter, the behaviors and dynamics of complex systems. That means we tend to see events, parts and fragments when we are in fact, embedded within and surrounded by interconnected systems. There’s now a lot of research out there, including my own, that deep misconceptions about the dynamics of complex systems persist, even among highly educated adults. Here’s the short version: when faced with dynamically complex systems—with multiple feedbacks, time delays, nonlinearities, and accumulations—performance is suboptimal, at best.

What to do? Facing a similar question, Buckminster Fuller once said: “If you want to teach people a new way of thinking, don’t bother trying to teach them. Instead, give them a tool, the use of which will lead to new ways of thinking.”

The good news is, new tools and new frameworks are coming. Here are just a few examples (send me more if you have them):

Camp Snowball: A summer “camp” experience that brings together students, parents, educators, and business and community leaders to build everyone’s capacity around systems thinking, sustainability and leading in the 21st century.

WorldLink: An innovative media, education and civic engagement organization dedicated to cultivating a generation of “design scientists” who can creatively respond to the most pressing issues of our time. See NOURISH (using public TV and school curriculum to explore food and food systems).

The GeoDome: Using immersive projection design to understand and have a tangible experience of the planet as a living system.

Quest to Learn: A game-based public school in New York City (brainchild of Katie Salen and team) and in particular it’s “need to know” approach to building twenty-first century skills like systems thinking, creative problem-solving, collaboration, time management and identity formation.

PBS Learning Media: I’m working with PBS now to integrate systems literacy tools and concepts into digital media for both educators and students. The pilot will be available in the fall. Exciting!

Student-created simulations of complex systems, game-based learning, portable “learning” domes, repurposed digital media — Bucky, I think, would be delighted by these ways of making invisible connections, visible.

Synergy is just one reason I’ve fallen head over heals for Bucky, that stocky, gentle genius with the owl eyes and coke-bottle glasses. Read my book about him (when it comes out) and you’ll have fun discovering the other 9 reasons why Bucky is truly a troubadour for our times.

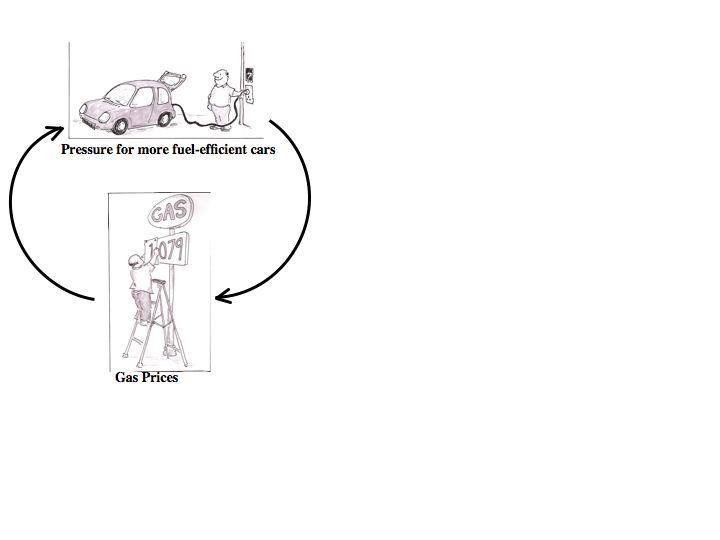

If we walk around the loop, it reads like this:

If we walk around the loop, it reads like this: