All Systems Go! Becoming a “Systems-Smart” Generation

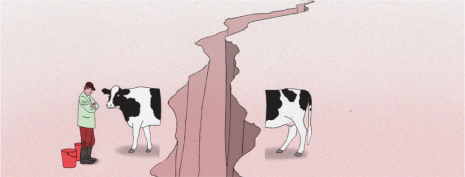

Illustration by Guy Billout

Try this: Find a young person between the ages of four and twenty-four. Show them a picture of a cow and ask, “If you cut a cow in half, do you get two cows?” Even the four-year-old will shout, “No way!” Children understand that a cow has certain parts—hearts, lungs, legs, brain, and more—that belong together and have to be arranged in a certain way for the cow to live. You cannot have the tail in the front and the nose in the back.

As adults, it is easy to miss this simple truth: a cow is a complex, living system, in the same way that the human body, a family, a classroom, a community, an organization, or an ocean is. A system is composed of parts and processes that interact over time—often in closed-loop patterns of cause and effect—to serve some purpose or function. Living systems, unlike a collection or “heap of stuff ,” share similar characteristics. In systems, it matters how the parts are arranged. at is why a cow cannot have the tail in the front and the nose in the back. And why a stomach does not work on its own, and the body does not work without a stomach. And systems often are connected to or nested within other systems (for instance, a person may be nested within a family, school, ecosystem, community, and nation).

Make the Shift: Systems Are the Context

Sounds simple, right? But here is the challenge: much of today’s education remains focused on discrete disciplines—for example, math, science, and English. Science is taught in one class. The bell rings. The student moves onto math and then, perhaps, to English—and never the twain shall meet. Such a fragmented approach reinforces the notion that knowledge is made up of many unrelated parts, leaving students well-trained to cope with obstacle-type or technical-based problems but less prepared to explore and understand complex systems issues. In medicine, for example, obstacle-type problems are those that can be clearly targeted and fixed, such as a broken arm or an acute disease, like appendicitis. A systems approach is more effective for chronic and complex diseases, such as diabetes, where the interaction of factors—lifestyle, family history, environment, etc.—also plays a role.

Issues such as climate change, economic breakdowns, food insecurity, biodiversity loss, and escalating conflict are matters not only of science, but also of geography, economics, philosophy, and history. They cut across several disciplines and are best understood when these domains are addressed together. Students and adults must be able to see such important issues as systems— elements interacting and affecting one another. In the case of climate change, a systems view shows the link between politics, policy (for example, legislation related to carbon emissions and deforestation), the natural sciences (particularly forests, which help stabilize the climate by absorbing heat-trap- ping emissions from factories and vehicles), and a person’s own consumption habits. Without a systems view, the complexity can be daunting, and the result is often policy resistance or, worse yet, polarization and political paralysis.

The excerpt above is from an article I recently wrote for World Watch Institute’s 2017 State of the World Report. For the complete article, click here.

Thank you to Draper L. Kauffman Jr., author of Systems I: An Introduction to Systems Thinking, for your inspired cow question, posed now over 30 years ago.

Illustration: Guy Billout, Art Direction, Milton Glaser. From “Connected Wisdom: Living Stories about Living Systems” by L. Booth Sweeney