Leaning into Complexity: Young Leaders of Systems Change

HI EVERYONE!

It’s been a while. I hope you’re all staying healthy and finding a new rhythm during these challenging times. Like many of you, I feel our systems-based work is more urgent than ever.

Young people are watching. They’re worrying. From climate change to our current pandemic, adults don’t seem to have the answers. Even the very young now know that events in China can close down schools, economies, and be responsible for deaths thousands of miles away. They know in their bones they’re living in a tightly interconnected web (what Martin Luther King called “the interrelated structure of reality”).

Here are the questions I go to bed with and wake up in the morning thinking about: How can we encourage young people to understand and lean into the complexity they’re experiencing and, see that complexity as a feature of their world — a guide – rather than the enemy? How can we help them to look to the other side of the hardship and disruption they’re experiencing, to feel confident they can solve complex problems and together, innovate their way to healthier futures? Curious how you would answer those questions. For me, whole-systems learning — experiential opportunities to improve our ability to see, understand and work with interdependent systems — is one answer. For an example of “whole-systems learning” in action, partnership, please read on.

————————————————-

During a recent climate change rally, on an unusually warm day late last fall, I noticed two young women holding this sign:

They laughed when I asked them about systems change. They had to admit, systems change sounded like a good idea but they weren’t sure how to actually do systems change. Fair enough. Most adults don’t either.

Last Fall, I started working with teenagers and young adults through a local non-profit called SparkShare (https://www.sparkshare.org/), a non-profit dedicated to supporting young people to solve problems across differences. During a one-day systems change summit, I worked with 100 teen leaders in 13 groups from the Boston area, all of whom are focused on solving complex challenges in their communities — from vaping, substance abuse, racial equity, to youth employment, climate change and safer streets.

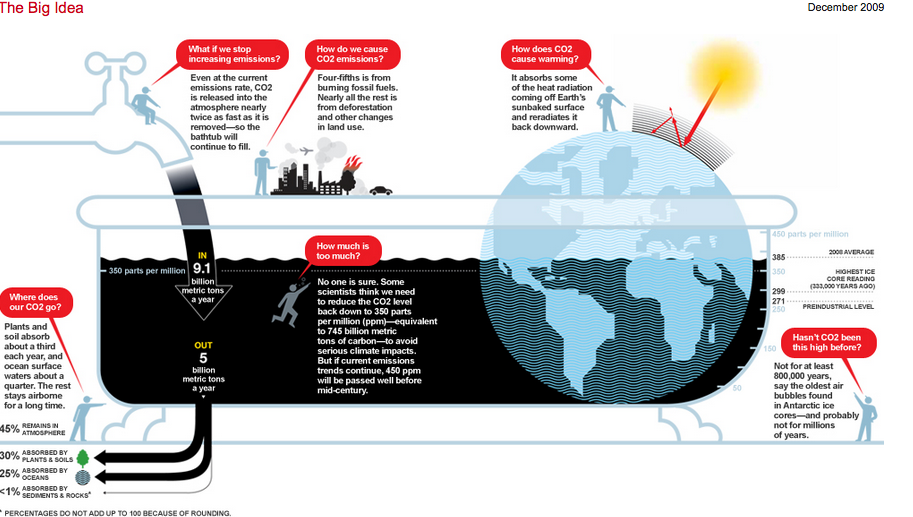

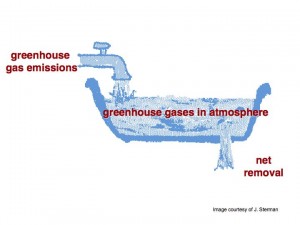

During the summit, the youth groups focused on “helping the system to see itself” through systems mapping. We also built in plenty of opportunities to envision “future states” (Buckminster Fuller’s term), cross-pollinate between and among the groups, make real commitments for action and have fun! In the month leading up to the summit, I worked with each group virtually to shape a strong systems question, one that incorporated change over time. I opened the summit by thanking some of my “teachers” including Dana Meadows, Ruth Rominger, John Sterman, Dennis Meadows, and Peter Senge, and introduced the concept of systems, system dynamics and the broader field of systems change. At the close, I let them know they were not alone and encouraged them to connect with the growing number of people around the world who understand and use systems-based approaches in a variety of professions.

Their reaction to the day was electric! You can see a short video below:

Most exciting were the practical actions groups took after the summit. One team used their systems mapping experience to better understand the multiple factors that drive teen vaping, concluding that they had to reach their peers in different ways, reduce access, and engage adults. After the summit, they partnered with a manufacturer of vaping detectors and are now working with school administration to get vaping detectors into bathrooms at their high school.

Together with the team at Sparkshare, we’re working to make systems change a core part of how their youth partners work together to positively impact their communities, and develop the skills to become the future problem solvers our world desperately needs. We’re actively looking for funding to create a scaleable systems change “hub” offering:

- Virtual, in-person labs for whole-systems learning, rapid prototyping

- Collaborative network building

- Peer and expert coaching

- Virtual, in-person community

- Question-led database

- Protocols that enable partners to test solutions and learn from what works (and what doesn’t).

If you can help us make this systems change “hub” a reality, please do be in touch. I’ll be announcing upcoming “whole-systems learning” opporutnities over the next few months via this blog.

Take good care!

What is Systems Change: Fostering health in systems through coordinated shifts in narratives, relationships, networks and structures.