A Snow Day Lesson

In this blog I write about systems.

What’s tricky here is that systems — two or more parts that interact to form a whole — are often hard to see.

If you think of it, have you ever seen a system walking around? Why not? Well, for the most part we don’t actually see the connections that make up systems. We have to imagine how this influences that.

I was reminded of this during yet another snowstorm last week. With school closed, my two boys were having a ball, and then, as the afternoon crept in, the laughing was replaced by arguing. What started out as a sharp word or two, ending up in a not-so-playful snowball fight.

I was reminded of this during yet another snowstorm last week. With school closed, my two boys were having a ball, and then, as the afternoon crept in, the laughing was replaced by arguing. What started out as a sharp word or two, ending up in a not-so-playful snowball fight.

Was this simply too much of good thing? To find out, I took each one aside, and listened while each told their version.

They both told a similar story: an annoyed comment from one, led the other to comment back, which led to a poke, then… (you know the scenario). In both of their explanations, I heard a common pattern – often seen in systems – called escalation. (If you don’t have children, just think about any situation that escalates like the old advertising campaigns for Coke and Pepsi, competing street gangs, or the current situation between Palestine and Israel. Siblings, companies and countries can all be viewed as “living systems”; the difference is the scale.)

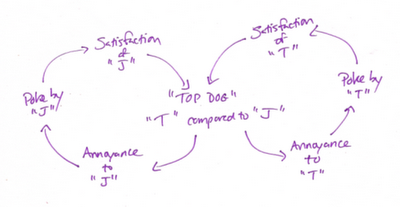

Whether you’ve studied systems or not, you know the pattern I saw. One party does something that is seen as a threat by another party so the other party responds in kind, increasing the threat to the first party. This results in even more threatening actions by the first party and the cycle continues. Seeing this pattern I drew the following picture with my boys:

(Here’s how you read it: Start in the middle. One boy, let’s call him “J”, makes a move to be more awesome than the other. Now, moving to the bottom of the right-hand loop, we see this annoys “T”, who then throws a poke of some sort at his brother. “T”, feeling he now has the leg up, then probably expresses some level of satisfaction. Then the cycle continues on the left-hand side, with “J” now feeling annoyed at “T” and so on.)

When I asked: “Would you say this is what’s going on?” they both agreed immediately but then quickly started talking over each other.

“Look,” one of them said, pointing to the diagram, “it’s a figure eight lying on its side.” The symbol of infinity.

“This thing could go on forever,” one moaned.

“And just keep getting worse,” the other groaned.

As we talked about it, the growing conflict was driven by each one trying to “out-cool” or “top-dog” the other. The more “cool” behavior one kid put on, the more the other wanted to squash it. As it turns out, one was particularly good at “poking” and the other one was good at “squashing”.

For that one snowy afternoon (with their Mom at her wit’s end), they saw themselves as part of the “system”, rather than separate from it. They “got” that focusing on just one of them wasn’t going to solve the problem. When they could see how their actions were actually fueling the actions of the other (with the help of a simple picture) they then were able to talk about how they might break the cycle.

When I asked what they could do differently, the answer came easily. The poker would lighten up on the poking, and the squasher wouldn’t squash so much.

When our children learn to see systems they eventually learn to see themselves “in” and not outside of situations. When they see that nothing stands alone, they begin to see that my bully is your bully, your food shortage is my food shortage, my climate is your climate. They learn to stop jumping to blame a single cause for the challenges they encounter and instead, try to track the a variety of interacting causes, effects and unintended impacts. They learn to move beyond laundry lists and look for more web-like patterns of cause and effect in their everyday lives.

Does all of this really happen when we talk to our children about systems?

We’re expecting another snow day this week. I’ll let you know how it goes.