An article in this week’s New York Times is a causing quite a brouhaha among fans of systems thinking. It seems that the Army is fed up with Powerpoint. (We Have Met the Enemy and He is Powerpoint, April 26, 2010)

Hallelujah!

But wait. Why are we celebrating?

Like many of us in the applied systems theory field, the Army (and in particular, General McMaster) has recognized that, “some problems in the world are not bullet-izable.” So the complexity of the Afghan situation cannot be condensed into bullet points, after all. PowerPoint, a favorite tool of the military to convey vast amounts of information, is under fire because, as General McMaster points out, it takes no account of interconnections and interrelationships among political, economic and ethnic forces.

General McMaster, we the scientists, practitioners and educators in the burgeoning field of applied systems science applaud you with one hand. We agree with you that problem solving requires a focus on interconnections, rather than on parts in isolation. Indeed, if you look around you’ll see a systems approach is driving the search for solutions for many of the problems we face in the environment, engineering, and in human societies. More and more, we see food, climate, childhood obesity, poverty, energy and other global challenges “systems” issues.

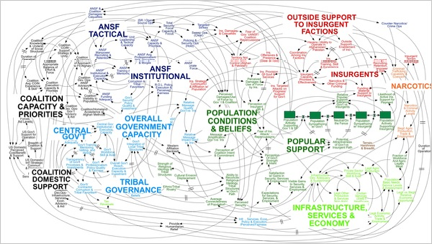

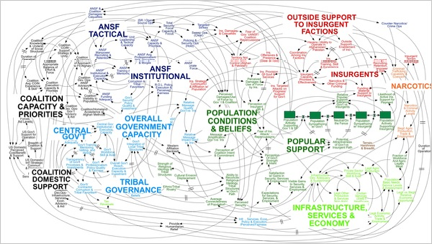

Yet when the interconnections and interrelationships of American military strategy were represented (as they were in this PowerPoint slide shown in Kabul), General McChrystal brushed it off as too complex and therefore not understandable.

General McChrystal brushed it off as too complex and therefore not understandable.

What’s a leader to do? Most leaders are required to drive action. They must clearly state a goal, line up a set of actions, exert pressure, and then reach the goal. Many leaders would agree that when lining up strategy, bullet points over-simplify and in the end, mislead. Yet complex systems maps are, well, too complex.

Let’s pause here for a moment to ask the elephant-in-the-room question: How did we get here? How did we get so bullet point and PowerPoint obsessed?

Of course, that could be the topic of a much longer blog (or book) but here is one, short answer: We Americans are encouraged to focus on objects rather than relationships.

In his book, The Geography of Thought: How Asians and Westerners Think Differently…and Why (2003), cognitive psychologist Richard Nisbett reports on studies conducted by developmental psychologists with American children. American school children and college students tended to group objects (such as a cow, a chicken and grass) by their taxonomic category. Chinese school children and college students, however, grouped objects based on interrelationships. For example, American students would group a cow with a chicken because they were both animals whereas Chinese students would be more likely to put the cow and grass together because the “cow eats the grass”. Referring to a similar study conducted with American and Japanese children, Nisbett observes: “American children are learning that the world is mostly a place with objects, Japanese children that the world is mostly about relationships.”

There are many other influences, such as language structure, compartmentalization of disciplines in school, and more. It’s no wonder our military leaders get antsy when they see a complex systems map. Most Americans, including our military, industry and government leaders, were not taught to think systemically; we were taught that the best way to understand a subject was to analyze it or break it up into parts.

Thinking in terms of systems doesn’t have to be hard. And it doesn’t have to replace bullet pointed lists and the 2×2 matrix. In many instances, it simply requires a perception shift from, for example, focusing on parts and fragments to tracing interconnections and the often surprising dynamics created by closed loops of cause and effect.*

In my classes and talks, I encourage students and audiences to be suspect of information that is presented as discrete (bullet point lists, for instance). When you see the world in terms of interconnections, networks and systems, you make a perspective shift:

From: Discrete information –> To: Closed Loops of Cause & Effect

When presented with bullet points, ask questions. Probe how those elements may be interconnected in closed loops of causality. Imagine you are in the audience as a presenter concludes his or her presentation with a list of “Next Steps.” One step is to “train future leaders” in a specific research or problem-solving approach. The next step is to “increase funding for special projects”. Rather that nodding your head and swallowing the list whole, pause, and ask: “What will happen if we train more future leaders? Will that have some impact on the our ability to ‘increase funding for special projects’?” Look beyond the bullet points for multiple causes, effects and unintended or unexpected impacts.

“What?!” you say? Ask more questions? There’s no reward in that! As a general, manager, or any type of leader, I need to know where to exert my effort, my resources and my attention.

I can offer you this promise: If you find ways to work with your team to map either the current or desired reality of a complex issue, using pencil & paper sketches, PowerPoint or computer models, you will: a) uncover a host of unintended consequences that emerge from the interactions among your decisions, b) discover unforeseen leverage points, and c) make more informed decisions and policy changes that will likely lead to positive results. As a side benefit, you will be more likely to get off that problem solving treadmill, where our “solutions” often only create more problems or make the original problem worse and, as a result of creating causal models as a group, you will experience greater clarity and learning among group members. (By the way, if you don’t do these things, Joseph Campbell has a warning for you: “People who don’t have a concept of the whole, can do very unfortunate things…”).

And what about PowerPoint? Is it such an evil tool?

In my opinion, the Army missed the point about PowerPoint. PowerPoint, like any tool, it is only as good as the person using it. You can dumb down complexity by parsing out information into mind-numbing sets of bullet points. You can also use PowerPoint to represent complex interrelationships and dynamics by using arrows, icons and builds.  The mistake made with the American military map is that too large a serving of spaghetti was put on one plate, instead of showing one noodle (or causal link), and one domain (e.g., tribal governance) at a time. (My assumption here though, is that since the map was created by the highly-skilled PA Consulting Group, the map was presented to the generals one section at a time).

The mistake made with the American military map is that too large a serving of spaghetti was put on one plate, instead of showing one noodle (or causal link), and one domain (e.g., tribal governance) at a time. (My assumption here though, is that since the map was created by the highly-skilled PA Consulting Group, the map was presented to the generals one section at a time).

Whether you’re an educator, business leader, physician, urban planner, engineer, community organizer, or military general, it’s time to be curious about how this is connected to that. We all need to move beyond laundry list or bullet point thinking to seeing and thinking about patterns of interaction, networks and other lines of inquiry and problem solving that more closely matches the more interdependent, complex world we live in.

L. Booth Sweeney, Concord, MA

For another system dynamics perspective from on the New York Times article, see this post from Chris Soderquist.

Many thanks to Gale Pryor and John Sweeney for their thoughtful commentary on early drafts of this post).

*What are “closed loops of cause and effect?”: When we “get” the idea of closed loops (vs. straight lines) of cause and effect, we understand that closed “feedback loops”— circular loops of mutual causality that amplify change — underlie the spread of a rumor, the growth of a virus, or a successful person’s willingness to take on more work. Reinforcing feedback loops act as engines of growth: change in a system feeds back to cause even more change in the system.

We also look for balancing or self-regulating feedback — a set of interactions that return a system (like your body, an ecosystem, market systems) back to a state of equilibrium. By their very nature, balancing feedback works to bring things to a desired state and keep them there. When we understand balancing feedback, we stop using our thermostat like a gas pedal, increasing or decreasing the temperature to suit our moment-by-moment needs. Rather we let the internal feedback structure do its work, allowing the temperature to self-adjust to a desired temperature.