The Little Gold Sticker “Effect”

How do we nurture children’s capacity to “think about systems” through everyday conversations and activities?

Many of you know I’ve been asking this question for a long time.

These days, I’m thrilled to be part of a movement to help children develop “systems literacy“, “systems thinking dispositions“, and other systems thinking “habits of mind” (and here). Today, children and the adults who teach them can learn to think about and work with systems through camps like Camp Snowball and Design Camp, through innovative learning programs from SEED, the Institute of Play (see related blog) and Lego Serious Play and from systems educators at The Waters Foundation, the Creative Learning Exchange and The Cloud Institute, by reading blogs by Beth Sawin, Tim Joy, Tom Fiddaman (especially when he talks about his kids), Pegasus and many more (tell me who I’ve missed!)

I now have to add my most recent book — Connected Wisdom: Living Stories about Living Systems (SEED/Chelsea Green)*– to the list of good things that encourage systems literacy.

I now have to add my most recent book — Connected Wisdom: Living Stories about Living Systems (SEED/Chelsea Green)*– to the list of good things that encourage systems literacy.

I found out today that the book and children’s CD won at the New York Book Festival. (The CD won last month at the San Francisco book festival).

That’s good news!

What may be even better news is that we now get to put those little gold “winner” stickers on the book and the CD.

Sure, it’s good to get the recognition (who couldn’t use a pat on the back), but mostly, it’s good because people will be pick up the book or CD, and share it with their children.

Sure, it’s good to get the recognition (who couldn’t use a pat on the back), but mostly, it’s good because people will be pick up the book or CD, and share it with their children.

Now that’s the really good news! As our children come to appreciate and see living systems in their everyday lives, we can confirm for them what they already know: that their world is interconnected and dynamic, a tightly woven web of interrelated elements involving people, places, events and nature and, as such, is indeed purposeful and meaningful.

My deepest gratitude goes to Simone Amber, who listened to (and acted on!) my crazy idea to use folk tales as as a way to learn about the principles of living systems. And to all who have been on this journey with me for past fifteen years, thank you for your continued encouragement. It has made a world of difference to me. For those of you who are new, welcome!

————————————————————————–

*The Connected Wisdom book and CD is a collaborative effort with three first-class artists – Milton Glaser, recipient of the National Medal of Arts is the book designer, Guy Billout is the award-winning illustrator and Courtney Campbell is the wildly talented children’s singer/songwriter. Funding for Connected Wisdom was provided by SEED. It is currently translated into nine languages including English, Portuguese, French, Arabic, Chinese, Spanish, Russian, Dutch and Hungarian.

This is what the poet Judy Sorum Brown has to say about the book:

“Artfully, beautifully, playfully, seriously, clearly Linda Booth Sweeney invites us to join her in a deeper understanding of the profound principles of living systems. Tapping wisdom connected to many cultures and many times, Linda weaves memorable simple stories into a tapestry holding enormous complexity. A book that is at once a work of art, a representation of science, and an invitation to think more deeply and playfully, Connected Wisdom is a gift. Whether the reader is six or sixty, it matters not. These pages open us more fully to the world around us.”

Ok. Just one more, from the children’s troubadour and author, Raffi:

“The moment you touch and open this book, its wisdom is evident. This is the wisdom of wholes, of belonging, and connecting the dots to see the richer tapestry of life.”

To hear a preview of the Connected Wisdom CD, click here. Also for the academic-types among you (I’m one of them), my endnotes for Connected Wisdom can be found here.

For teachers:

Earth science and other educators looking to effectively engage young people while meeting state and national standards will find the Connected Wisdom book and CD invaluable resource that is easily linked to curriculum standards. For example, National Science Education Standards call for students in grades five through eight to study earth and life systems, including natural cycles, natural cycles, nature awareness, habitats and community (specifically, dependency of plants and animals on their habitat and each other) and, human influence on habitats (and in Canada, standards 4s1 and 4s3).

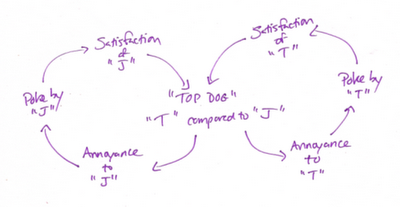

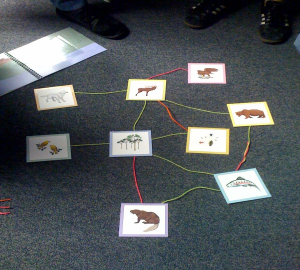

So, Lilly, at the tender of seven, got it. She explored the interconnections and dynamics of the farm and found that all roads (all wikki stix in this case) lead to the soil. In just a short half hour, she discovered the role soil plays in the health of crops, animals and people. With more time, she would have also likely discovered soil’s role in the cleanliness of water and the livelihoods of farmers. She might also have been guided to think about “systems” as an organizing framework to take home and apply, for instance to that escalating squabble with her brother or to preventing homework “burn-out.”

So, Lilly, at the tender of seven, got it. She explored the interconnections and dynamics of the farm and found that all roads (all wikki stix in this case) lead to the soil. In just a short half hour, she discovered the role soil plays in the health of crops, animals and people. With more time, she would have also likely discovered soil’s role in the cleanliness of water and the livelihoods of farmers. She might also have been guided to think about “systems” as an organizing framework to take home and apply, for instance to that escalating squabble with her brother or to preventing homework “burn-out.”