Food Systems, Climate Systems, Laundry Systems: The time for systems literacy is now!

Tell me, in what subjects are you literate?

Sounds like a question a college interviewer might ask. To be literate of course, means you have a good understanding of a particular subject, like a foreign language or mathematics. If you’re reading this, you probably have good English literacy. For others, science or engineering, or even our woodworking or gardening literacy is particularly strong.

If you listen closely to folks like Thomas Friedman, Michael Pollan, Nicholas Kristof, Wendell Berry and others, you’ll hear them asking for a new kind of literacy, one I call systems literacy.

This new literacy calls for us to “connect the dots”, to look at not just the parts but the interrelationships, patterns, and dynamics as well when faced with complex issues, or what Russ Ackoff use to call “wicked messes.” When we think in terms of systems, we toggle our focus between parts and wholes, between open loops and closed loops (where waste from one source can be “food” for another), between microcosms to macrocosms. We learn to see recurring patterns that exist among a wide variety of living systems and we use our understanding of those patterns to correct actions, anticipate unintended consequences, and produce learning.*

Why do we need another literacy? My favorite agrarian poet Wendell Berry says it so well:

“We seem to have been living for a long time on the assumption that we can safely deal with parts, leaving the whole to take care of itself. But now the news from everywhere is that we have to begin gathering up the scattered pieces, figuring out where they belong, and putting them back together. For the parts can be reconciled to one another only within the pattern of the whole thing to which they belong.” (from The Way of Ignorance, pg. 77)

Most Americans, including our industry and government leaders, were taught that the best way to understand a subject was to analyze it or break it up into parts. Where were we taught the skills of seeing and understanding systems of complex causes and effect relationships and unintended impacts?

Yet these are the skills we need to create sustainable communities, and to address pressing issues such as vulnerable food systems, global warming, childhood obesity, unstable energy relationships, environmental degradation and more.

When we are systems literate, we can…

… stop jumping to blame a single cause for the challenges we encounter and instead, look for multiple causes, effects and unintended impacts.

…move beyond laundry lists and bullet points, to seeing patterns of interaction that more closely match the more interdependent, complex world we live in.

…get off that problem solving treadmill, where our “solutions” often only create more problems or make the original problem worse.

When we are systems literate, we look at the economy, the climate, education, energy, poverty, waste, disease, sustainable communities as systems issues. We see that nothing stands alone, which means that my climate is your climate, your infectious disease is my infectious disease, your food shortage is my food shortage.

Where do you start? Perhaps you pick up a copy of Donella Meadows book “Thinking in Systems” or Peter Senge’s classic The Fifth Discipline, or Fritjof Capra’s The Web of Life or the just released systems education book, Tracing Connections. (For other suggestions, look at the systems literacy resources on my site).

Or you simply try adding the word “system” as you talk about everyday issues, big and small, such as laundry (system), family (system), classroom (system), food (system), waste (system), climate (system), and so on. By adding the word system, we begin to look for interconnections, closing loops of material and information flows, anticipating time delays and the inertia created by stocks (or accumulations).

When we think of the laundry as a system, we shift our focus from the pile of laundry to the many interrelated factors influencing that pile: children, dogs, towels that could be used more than once, etc.

When we think of farms as living systems, we see the parts and processes of a farm include the farmer, animals, crops, insects, soil, weather and natural cycles, such as the water cycle, as connected to and nested in each other.

When we think of farms as living systems, we see the parts and processes of a farm include the farmer, animals, crops, insects, soil, weather and natural cycles, such as the water cycle, as connected to and nested in each other.

We also see the farm as part of a larger food production system that includes natural and human resources, waste, food processing, distributors and consumers, and we see the farm’s role in influencing other systems such as health care, energy independence and climate.

Everyday, I see more opportunities for developing systems literacy. In the last fifteen years, a growing number of schools in the U.S. and around the world have begun in earnest to teach students systems thinking. Several State Departments of Education are including systems thinking and “Education for Sustainability” (EFS), or learning that promotes understanding of the interconnectedness of the environment, economy, and society, as a requirement for middle school science standards. The MacArthur Foundation just awarded a major grant for a project focused on developing systems thinking in middle school students and developing new curriculum for teachers across disciplines.

Just as our nation has improved its math literacy and science literacy, the time has come for us all to support efforts to develop systems literacy.

*Scientists and educators in the burgeoning field of systems science describe a living system as patterns of interrelationships among parts that continually affect one another over time. Increasingly, a systems approach is driving the search for solutions for the problems we face in the environment, engineering, and in human societies. Systems literacy combines conceptual knowledge (knowledge of system properties and behaviors) and reasoning skills (the ability to locate situations in wider contexts, see multiple levels of perspective within a system, trace complex interrelationships, look for endogenous or “within system” influences, be aware of changing behavior over time, and recognize recurring patterns that exist within a wide variety of systems. See here for more on the principles and habits of mind related to systems literacy.

I spent the most extraordinary week with the

I spent the most extraordinary week with the

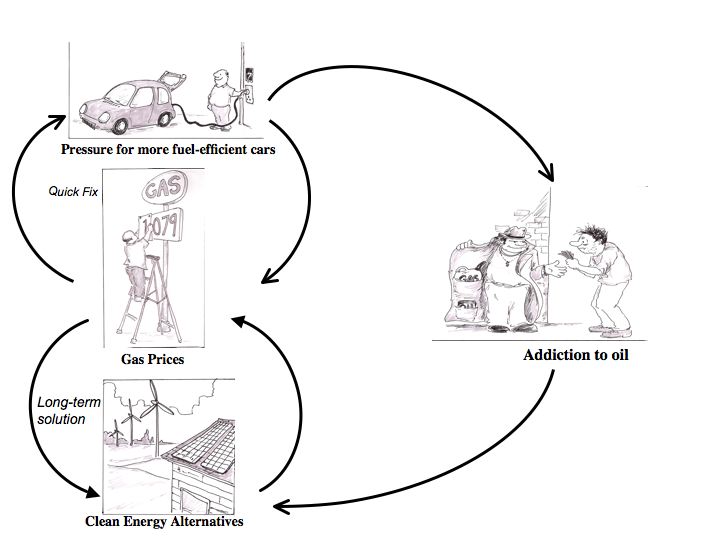

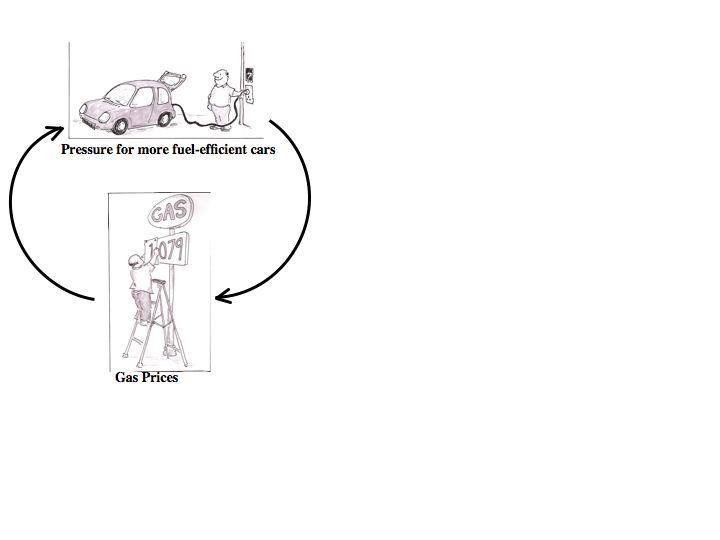

If we walk around the loop, it reads like this:

If we walk around the loop, it reads like this: