Shifting Patterns

Stories. We love them. They’re our most ancient form of education. And yet there’s often a mismatch between the stories we love to read to children and the way the world actually works.

It comes down to plot lines. Most children’s stories tend to feature some sort of straight line, often starting with a problem, followed by a reaction, and ending with a resolution. It’s one, linear pattern of connection:

A →B →C

A causes B, and B causes C. End of story.

Think about the children’s book I Know an Old Lady (by Rose Bonn and Alan Mill). It’s about an old lady who swallowed a fly:

I know an old lady who swallowed a spider

That wriggled and wriggled and tickled inside her.

She swallowed the spider to catch the fly.

But I don’t know why she swallowed the fly!

I guess she’ll die!

The old lady goes on to swallow a mouse, a cat, a dog, a cow, and, finally, a horse — all to catch a pesky little fly. What happens when she swallows the horse? “She dies, of course!”

Ok. So it’s not A →B→C, but A→ B→ C → D→ E→ F → G. End of story.

The story is dark, hilarious and a one-way pattern of connection, that is, a long, straight chain of events. Many things in a child’s life do happen in a straight line of cause-and-effect: turn up the volume on the TV and the sound increases. A causes B. Done.

But cause-and-effect is not always straight. Indeed it can be loopy, web-like, cascading.

(Hang in with me now. We’re going to enter the field of systems thinking. It may sound abstract but it is really practical stuff that is leading the way to solving some of the world’s most pressing problems*).

Let’s look at the loopy kind. In If You Give a Mouse a Cookie, a best-selling children’s story by Laura Joffe Numeroff (illustrated by Felicia Bond), the mouse wants a cookie, then a glass of milk and by the end of the story, he wants another cookie. Here’s how my eight-year-old nephew drew the chain of events in Numeroff’s story:

Unlike the Old Lady who swallowed that fly, this closed loop of cause and effect, feedsback on itself to amplify change. Even the youngest readers intuitively know that the story could go on forever and if left unchecked, the mouse is going to want more and more cookies. When we understand how reinforcing feedback loops work, for example, we see how events build on one another — and how a small change can “grow” into larger and larger consequences as the pattern of connections loops and loops around. Children encounter these reinforcing feedback loops everyday. Think of mean words on a playground, rising noise levels on the bus ride home or the spread of a rumor.

Young children can learn to “close the loop” and take advantage of reinforcing feedback. Think about saving money in the bank. It doesn’t take a math whiz to appreciate compound interest, which Albert Einstein once called “the most powerful force in the universe”: An increase in the amount of money in the bank increases interest payments. An increase in the interest payments compounds the initial increase of the amount of a child has in the bank. It’s not a far leap for kids to harness that same time of reinforcing feedback to grow, for instance, kindness in the classroom.

While reinforcing feedback loops act as engines of growth and decline, another closed loop of cause and effect — balancing loops — self-regulate and dampen change. By its very nature, balancing feedback works to brings things to a desired state and keep them there. Sometimes this is good (e.g. helping to keep a system in balance) and sometimes this is why we feel stuck.

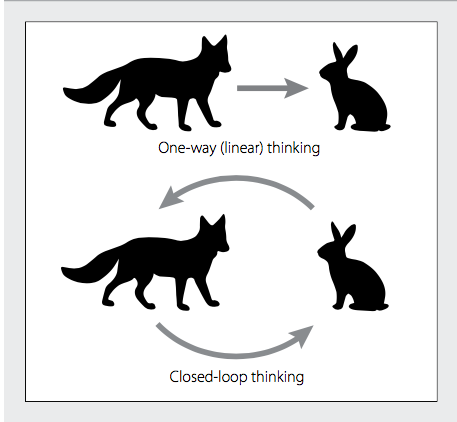

Image courtesy of World Watch 2017 State of the World Report

When we understand balancing feedback, we understand that predator-prey relationships in nature are not one-way (where the predator simply eats the prey), but rather is made up of a closed loop of cause and effect, with births and deaths of one species affects the population of the other.

Closer to home, when we understand balancing feedback, we stop using our thermostat like a gas pedal, increasing or decreasing the temperature to suit our moment-by-moment needs. Rather we let the internal feedback structure do its work, allowing the temperature to self-adjust to a desired temperature. (Indeed we live on a planet controlled by balancing feedback loops but that is another post!)

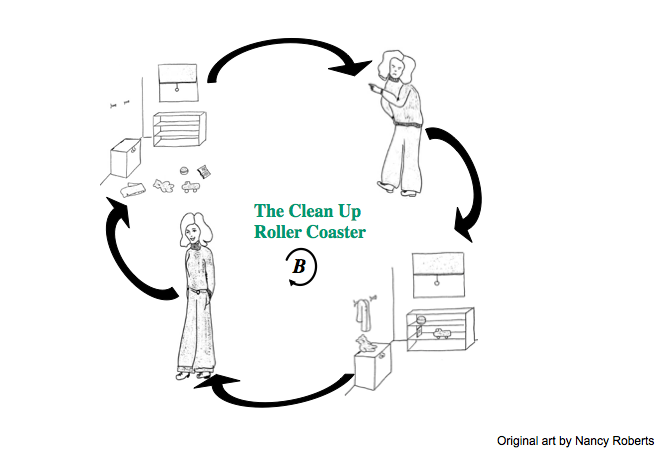

A child who understand the basic idea of balancing feedback has a better understanding why things get stuck, and what they can they do about it. Let’s use the example of a messy room and a child that is doesn’t want to clean it. Throughout the week, the parent may reminds him: clean up your room! The child on the other hand, is otherwise occupied. By the end of the week, the parent’s frustration is boiling over. Finally, the parent threatens a week of no TV or depending on the age, no cell phone and the child relents. When he shows his clean room, the parent is happy. But the next day, with the pressure off, he slowly reverts to his old habits and the room becomes messy again. Mid-way through the week, the parent’s frustration builds again, this time with more pressure. The room clean up roller coaster continues.

(What to do? One way out of this dilemma is for the parent and child to sit down together, and draw simple diagrams showing the situation as one sees it. Then together they can figure out how to change the pattern.)

Growing Little Systems Thinkers

Back to children’s stories. Don’t get me wrong. I love stories with all kinds of plot lines. I’ve written two myself. But a diet of all one-way plots doesn’t prepare our children for the diversity of real world patterns they will encounter.

So what can you do?

Encourage your little readers to be pattern detectives.

Encourage them to draw the patterns they see in stories. Then look beyond books to the cause-and-effect patterns they see on the playground, around the dinner table or on the front page of the newspaper.

By seeing these patterns, they will be more likely to stop jumping to blame a single cause for the challenges they encounter be curious about the multiple, interacting forces driving events and often, unintended impacts. As an added bonus, when children (and adults for that matter) see patterns, they are more likely to be able to understand them and when needed, to change them. (For an example with two siblings, read here).

Ask questions to focus on cause-and-effect:

o What happens next? (Keep asking. Sometimes you’ll find a drives b which drives c which loops back to drive more or less of a).

o How is this similar pattern similar to that? When they get older recognizing these patterns helps build a bridge between different disciplines in school. Bridging science and social studies they might ask: How is the growth of the bacteria we’re looking at through the microscope similar to the population growth in a particular region?

Whether we are 7 or 77, when we are aware of these closed loops of cause and effect, we are less likely to react to behaviors produced by them and more likely to be able to understand them and when needed, to change them.

Good Books for Little Systems Thinkers

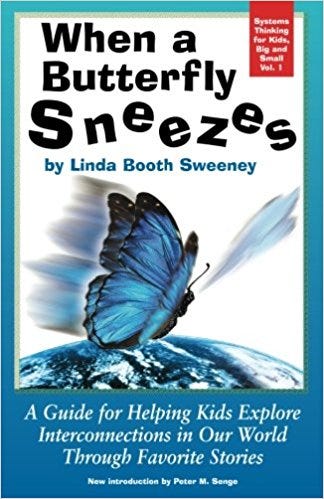

For an introduction to systems-based stories for little systems thinkers, see the 2018 version of When a Butterfly Sneezes: A Guide for Helping Kids Explore Interconnections in Our World Through Favorite Children’s Stories (2018, updated and revised with a new introduction by Peter Senge). For more on systems thinking, see: www.lindaboothsweeney.com.

Other Useful Links:

Systems Thinking in World folktales: see Connected Wisdom: Living Stories about Living Systems by L. Booth Sweeney.

Causality in science: see the Causal patterns in science work of the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Causality in children’s nonfiction: see author Melissa Stewart’s blog Celebrate Science (look for “cause and effect” books).

Systems stories in the classroom: Waters Foundation and Creative Learning Exchange (search resources for literature)

PBS Learning Media: see the Systems Literacy Collection

THANK YOU to Gale Pryor, Penny Noyce, Emily Rubin, Melissa Tackling , Eugene Pool and Christine Abely for your thoughtful feedback on this article.

Tags: children's stories, Conceptions of Causality, storytelling, systems thinking