Loops or Lines: What comes most naturally?

Outside Escola Municipal Jose Calil Filho

More than 50 students from the Escola Municipal Jose Calil Filho, an elementary school in Macae (about four hours north of Rio de Janerio) cram two-to-a-seat in a steamy classroom. It is the day before summer (and Christmas) break in Brazil and the tiny classroom is about to burst with excitement. These students, ranging in age from 8-11, are here to listen to a lady from the U.S. talk about something called “living systems”.

Sounds impossible, doesn’t it?

I would have thought so, but I was that lady and I couldn’t have been more impressed by the beautiful minds that greeted me that morning.

With students, teachers and SEED volunteers in Macae

I was there to pilot a workshop for SEED that integrated three “literacies”: systems, science and self-knowledge. Despite the steamy conditions, the students were curious, attentive and ready to learn.

Showing a straight line of causality (front row) and closed loops (second row)

Working in groups of three to four, the student-detectives were tasked with figuring out the connections, some obvious and some hidden, in a farm setting (using a systems playkit). Many students were surprised to discover, for instance, the central role chickens can play in the health of the cows and the pasture.

There’s much to report from that December workshop (you can read more about it here) but for readers of this blog I have to report an observation that continues to fascinate and challenge me:

When asked to show the interconnections on a farm (what influenced what), some students, seemingly regardless of age and gender, laid out a straight line of cause and effect (see picture above), while others (see the second row) created twisty, curvy connections that, occasionally, looped back on themselves (what we would call a feedback loop). (To learn about feedback loops in farm settings, see the Healthy Chickens, Healthy Pastures Curriculum Guide).

Badgered by Bateson

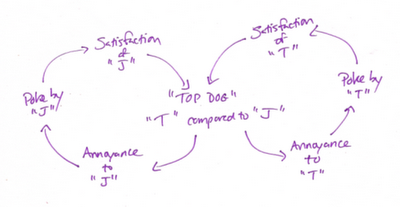

I remember being a little annoyed by Gregory Bateson’s claim that: “Adults have a chronic inability to understand cyclical, patterned phenomena such as interpersonal relationships and a variety of biological processes.”

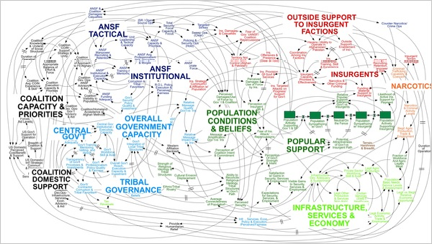

“Chronic inability”. Really? After investigating children’s and adult’s intuitive understandings of complex systems for the past 15 years, I’ve concluded that Bateson was on to something. Deep misconceptions about the dynamics of complex systems — whether the focus is climate, food, energy, obesity, or the environment — do exist, even among highly educated adults (see my research with John Sterman and colleagues, and Harvard’s Understanding of Consequence Project, for a multitude of examples). In my own research, I found that a significant number of students and adults used “open-loop” or one-way causal thinking when “closed-loop” causality or feedback was present, for instance, in situations involving predator-prey relationships or savings accounts.

Caution: Straight Line Thinking Can Be Dangerous

These deep misconceptions can be dangerous. In the natural world, we know that health and renewal occur through closed-loop cycles — water, oxygen, nitrogen, even solar. Yet when we disrupt these natural cycles*, we see big consequences — famine, flooding, and more. And then there is policy resistance, when the solutions to problems often make the problem worse. Think road building programs meant to reduce congestion that end up increasing traffic, delays and pollution. Or flood control efforts such as levees and dams that prevent the natural dispersion of excess water and so have led to more floods. John Sterman, who gives us these examples, argues that “policy resistance arises because we do not understand the full range of feedbacks operating in the system.”

The costs of fixing any one these problems is high. The cost of learning about cycles and feedback is low.

Back to the question of loop and lines. What led some students to straight lines and others to loops? I don’t have the answers yet but I’m hoping there are others out there who will think about this question with me. In the meantime, I’m going back to George Richardson’s Feedback Thought in Social Science and Systems Theory for inspiration.

Please be in touch. I’m curious to hear your thoughts.

Loops…

…vs. lines

________________________________________________________

NOTES: *For example, urban sprawl and the paving over of wetlands, grasslands and forests often disrupts nutrient, animal and water cycles. Ground that is unpaved absorbs water and stores it for use by plants. With more pavement, less water is absorbed by the ground which means there is less water for plants to absorb.