Systems Thinking + The Obama Code

What if the President of United States was a systems thinker? What if he talked about systems — rather than fragments — as the context for his decisions and policy making? What if he showed us that it is possible to stop operating from crisis to crisis, and to act in a more integrated, less reactive way?

What if the President of United States was a systems thinker? What if he talked about systems — rather than fragments — as the context for his decisions and policy making? What if he showed us that it is possible to stop operating from crisis to crisis, and to act in a more integrated, less reactive way?

This seems like a bunch of far-out ideas, right?

Not according to George Lakoff , professor of cognitive linguistics at U.C. Berkeley. In The Obama Code, Lakoff describes seven “crucial intellectual moves” that are behind Obama’s code of conduct. One of these seven moves (number six on the list) is Obama’s understanding of “systemic causation” versus “direct causation.”

Now, if you’re not a linguist, what does systemic causation mean, and how is it different than direct causation?

Let’s look at the difference by looking at the story of Laurie (hang in here with me, we’ll get back to Obama):

Laurie was in trouble. Her new consulting job was great for the first few months but now projects were piling up. She was missing deadlines, her e-mail box was full and every voice mail was marked “urgent.” At home, she found herself distracted and testy, snapping at the kids for no particular reason.

At a lunch meeting one day, while her colleagues engaged in a staccato thumb war on their PDA’s, Laurie waited impatiently for her laptop to boot up. The next week, she found herself wandering the halls, wasting precious time and unable to find her colleagues for the weekly lunch meeting. She found out later that the meeting had been moved; everyone else had picked up the message on their PDAs. When her boss teased her about joining the 21st century, she decided something had to change, and fast.

That evening, she got on-line and bought the fastest PDA she could find. Within 24 hours, she had it loaded up with all of her contact information and “to do” lists. Now, when she wanted to contact a client or send a document, she could do it all from one pocket-sized machine.

For a few months, Laurie felt like she was getting on top of her work. She found herself firing off e-mails at all times of day and in all kinds of locations: at the breakfast table, at soccer games, in the grocery store, even while her kids were taking a bath. It became a game to see how quickly she could respond to clients’ requests. Laurie was hooked.

As her response time began to improve, her clients settled down and her anxiety began to wane. As the pressure decreased and her productivity went up, she did what most people would do: she began to take on more work. After a few months, Laurie started to notice she was drinking more coffee to keep up the pace, and that anxious feeling started to creep in again. As she took on more work, the pressure increased and her ability to get it all done, even with the PDA, began to decrease. In the end, she was more tired and more anxious than she was before she purchased the PDA.

What happened? Laurie did what most of us would do when faced with a problem: she found a way to make the problem go away. Let’s take a look at the way Laurie “solved” her problem:

PROBLEM (Lack of productivity) —> SOLUTION (Time-saving device).

Laurie solved her problem by finding a clear and definite way out, taking a straight line from the problem to the solution. A solves B, end of story. This is what Lakoff calls direct causation. After implementing “the solution” Laurie thinks she solved the problem, yet her solution only makes the original problem worse.

How did Laurie get into this position? Just like Laurie, most of us have been conditioned to think in terms of straight lines. A fire breaks out in the neighborhood, quick, call the fire department. A teacher is out sick, call in a substitute. Step on a rusty nail, call the doctor and get a tetnus shot. The school roof is leaking, fix it. The market is down – sell (or buy). In these situations, we react, in the moment, to a problem that is well-defined. We go back to these straight line – A —> B – solutions because the problem usually goes away.

Yet many of the challenges we encounter are not made up of simple straight lines but patterns of interaction that better resemble loops, webs and networks. What’s more, many of life’s challenges are dynamic, changing over time, not static, single events we can address individually. Many people learn this when they become parents or managers. A congratulatory pat on the back to one child can send a sibling into a green-eyed tizzy. As a manager, you learn that a golf outing billed as a team building day becomes a “wicked mess” when members of your team don’t play golf. Rather than straight lines, these messy real-life challenges are more like systems. They’re made up of elements that interact and affect one another, often in ways we cannot see.

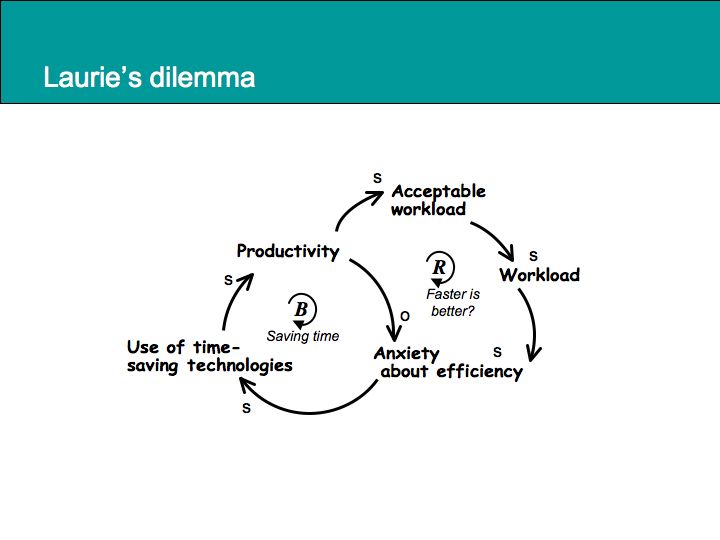

This is what Lakoff calls systemic causation. Understanding systemic causation means we see causality in terms of interrelationships, rather than fragments, and multiple causes and effects rather than isolated events. If Laurie were to look at her situation as a system, it might be drawn like this:

Now, of course, you don’t have to draw these systems maps when every time you find your self smack in the middle of what Russell Ackoff calls a “wicked mess”, but sometimes, it can really help.

When you make the system visible, you can then think more objectively about what link to break, or what additional loop you might add. For instance, looking at the above map, Laurie might see that the leverage lies in monitoring what she deems as “an acceptable workload.” Just because she can take on more work, doesn’t mean she should.

Laurie may also review her goals, however implicit they may be. She may decide her goal is to be successful and to have a happy, low-stress home life and so may find it acceptable not to take on additional client work. If her goal is to be the top consultant in the firm, and maintaining a steady workload is not an option, she may choose another systemic strategy. She may add a loop, in this case, a balancing loop. In Laurie’s case, she might add a “relaxation” loop, to manage or lower the stress she feels from an increased workload. In this balancing loop, as Laurie’s anxiety goes up, she manages it with some activity, such as meditation, yoga or walking.

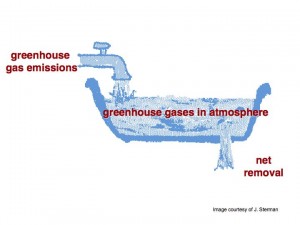

Back to Obama: the bottom line here is that by taking a systemic view — of climate change, of our schools, of the economy, of global conflicts — Obama is more likely to get our nation off the problem solving treadmill, where one “solution” only leads to a new problem, and onto more sustainable, more integrated strategies for change.